Best Sellers

Styylish History

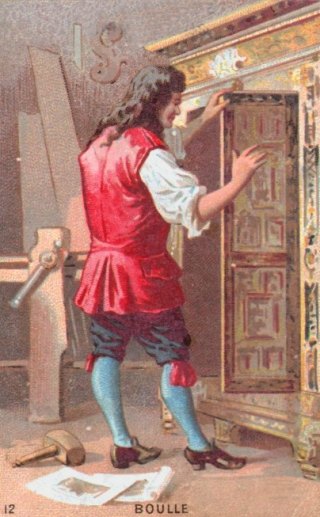

André-Charles Boulle | Legacy, History, And Works

André-Charles Boulle

A.C. Boulle was born November 11, 1642, and died February 28th, 1732, in Paris, France. Regarded as one of France’s most prestigious cabinetmakers, his artistry took Europe by storm during the 18th and 19th centuries.

As the dominating authority in marquetry (also known as inlay), it is no wonder how he earned the nickname le joailler du meuble, or “the furniture jeweler.”

Cabinetmakers across the continent heavily imitated his inlaying technique, which eventually was named after Boulle.

Although a highly talented cabinetmaker, Boulle also worked as an architect, bronze and mosaic, and created ornate monogram designs.

When Boulle was a youth, he studied drawing, painting, and sculpture. However, it was his gift as a furniture designer that boosted his status as Paris’s most talented craftsmen and carried his fame to the present.

The Style of Boulle

Pewter, ebony, and tortoiseshell marquetry, as well as brass decoration, define Boulle’s style.

Marquetry first emerged in 16th-century Italy. While he did not invent the technique, he took it to the next level, using exotic woods from India and South America.

He gathered inspiration from master drawings, prints, and paintings from legendary artists such as Raphael, Rubens, and 17th-century engraver Stefano Della Bella.

In 1754, Charles-Joseph Boulle hired German furniture designer Jean-François Oeben, from whom Jean-Henri Riesener inherited the family tradition.

Another novel design started by Boulle was incorporating bronze to protect fragile furniture parts. The effect, while practical, was extraordinarily innovative and opened the door for new decor.

Mascarons, claws, friezes, and foliage served to enhance console tables, bureaus, and cabinets. He also used bronze for clocks, decorative borders, candelabras, inkpots, and much more.

Boulle’s designs persisted successfully in France well into the 18th century. Boulle’s style became so famous that even some copper inlay against a black or red background in a given piece was known as Boulle.

In Paris, at the École Boulle, a college of fine arts and crafts and applied arts, students continue to practice his work in the Art of Inlay.

Boulle: A Family Of Artists

Boulle grew up in a wealthy and artistic Protestant family, which laid the foundations for his creative genius as a young adult.

He came from a line of naturalized royal cabinetmakers. His father, Jean Boulle (1616-?), was naturalized in 1676 and resided in the du Louvre, according to Royal Decree.

Pierre Boulle (ca. 1595-1649), his grandfather, was naturalized in 1675 and worked as a cabinetmaker to Louis XIII.

Additionally, Boulle had other famous family members, such as his mother’s sister, Marguerite Bahusche, married to Jacques Bunel de Blois (a favorite of Henri IV), were both well-known painters.

It is important to note that although A.C. Boulle was incredibly talented in his own right. But it helped that he came from a line of famous artisans employed by French kings.

Promotion To Royal Cabinetmaker

As a young man, Boulle wanted to become a painter, but his father forced him to become a cabinetmaker.

Boulle’s other artistic skills contributed in large part in his reputation as France’s most highly skilled craftsman.

Around 1669, Boulle began a four-year-long apprenticeship. During this time, he worked closely with his father in his atelier (studio) at the Louvre.

It was during this period that Boulle was closest to King Louis XIV and also discovered by Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619-1683). Colbert recommended Boulle as the successor of Jean Macé as the royal cabinetmaker in Versaille in 1672.

Boulle was just 30 years old by this time, but he already lived in the galleries of the Louvre with the king’s other favorite artisans.

This position was a sign of Royal favor and gave Boulle freedom from the rigorous constraints imposed by the trade guilds.

As the king’s royal cabinetmaker, Boulle was a chaser, gilder, and marquetry maker. Thanks to his skills, he designed most of the French furniture in the royal palaces.

Financial Struggles

The king granted Boulle permission to take private commissions from other notable figures. These patrons included King Philip V of Spain, the Duke of Bourbon, and the electors of Bavaria and Cologne.

At one point, his three workshops produced commodes, bureaux, armoires, pedestals, clock cases, and lighting fixtures.

Although Boulle and the men he employed were all incredibly talented and made pieces reflecting prices that matched their skills, Boulle struggled financially for most of his life.

Several factors contribute to his money struggles, one of the main ones being his compulsive collection of art.

Though he drew plenty of inspiration from his collection, it led to Boulle consistently struggling to pay his workers.

Additionally, he often failed to produce the work his affluent clients commissioned, which led to several formal attempts to seek permission from the Crown and arrest him for his debts.

In 1704, the King gave Boulle six months to get his affairs in order and settle things with his patrons.

Financial strife followed Boulle for most of his life. Tragically, a fire destroyed Boulle’s massive art collection and several other workshops in 1720.

This fire was devastating to the ébénistes, who lost precious building materials, appliances, models, and finished pieces.

Salvaged works sold, and Boulle requested financial assistance from the Regent. However, it’s unknown if he succeeded.

All in all, it is believed that the fire destroyed over 40,000 livres (a form of currency) and numerous works from Raphael, Michelangelo, and Rubens.

Afterward, he returned to his studio, overseeing it until his death in 1732. Although Boulle left his studio to his sons, they also inherited most of his debts.

Two of his sons, André-Charles Boulle II and Charles-Joseph Boulle, followed their father’s footsteps and became celebrated cabinetmakers in their own rights.

Materials

Boulle commanded mastery of several techniques and precious materials, particularly tortoiseshell, gilt bronze, and pewter.

Tortoiseshell

Favored for its durability and natural warmth, tortoiseshell is a rare and expensive material. Because of its marbled-red color, it works well with dark woods like ebony.

The combination of tortoiseshell and exotic woods created depth that became a signature in Boulle’s work.

Before he could use the thinly sliced material, the tortoiseshell first needed processing. This involved separating the parts of the animal’s shell by heating. Then, they were boiled in salt water to soften them and flattened under a press.

A hot iron could fuse the pieces, but a great deal of care was taken to prevent color loss.

Finally, a variety of methods were used to polish the end product.

Brass (Gilt Bronze)

Boulle was fortunate that as an ébéniste, he did not have to adhere to the restrictions imposed by the guild he belonged to.

This freedom left him plenty of room to experiment and create the pieces that made him famous. As he was a trained sculptor, he was able to design and cast his gilt bronze mounts for furniture.

A turning point in his career was the acquisition of a foundry in 1685, where he could make completely original designs. From there, he created chandeliers, clocks, firedogs, wall lights, and more.

Pewter

Another fine material Boulle often incorporated in his work was pewter. “Premier-partie” described pewter or brass inlay on tortoiseshell. “Contre-partie” was tortoiseshell inlay on brass or pewter.

Both methods produced a luxurious result. He heightened this effect with mother-of-pearl, stained horn, and tinted tortoiseshell.

Boulle: Innovations and Works

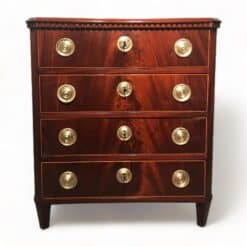

Boulle produced an enormous amount of work, including the creation of new furniture like the commode. Other designs included large, flat bureaus on legs, lounge tables, jewelry cases, and great pendulum clocks.

But his poor record-keeping, signatures, and a large number of imitators make identification a challenge.

He relied on the Bâtiments du Roi, the government organization responsible for building works at and around the royal residences, for recording his work.

However, these records didn’t identify new pieces with specific entry numbers or track the output.

When deciding if a piece is truly a Boulle, experts often look for several minute details. These include revealing subtleties in the marquetry, reused templates, and features of sculpted gilt-bronze mounts.

While sparse, there is somewhat of a paper trail for experts to look to when identifying Boulle’s works.

This includes a book of furniture designs and mounts engraved by Boulle and published by Pierre-Jean Mariette, workshop drawing, and legal documents from 1715 detailing an inventory of works in progress when his sons inherited his workshop.

Boulle’s definitive works include:

- Marquetry commodes, formerly in the Bibliothèque Mazarine

- Assorted cabinets, commodes, and tables at the Louvre, the Musée de Cluny and the Mobilier National

- Marriage coffers of the king in the San Donato collection

The Commode

The first prototype for the commode debuted in 1708, specifically for the king. It heavily reflected tastes of the late Louis XIV period, which prized opulence and grandiosity.

At the time, the bureau was the term for this design. It wasn’t until 1729 that people called this furniture a commode.

Boulle delivered two of these bureaus to the King at the Grand Trianon and became immediately successful.

Although some critics believed the four additional spiral legs needed for supporting the heavy bronze mounts and marble top were awkward, the design was immensely popular.

From 1710 to 1720, Boulle and his workshop produced five more examples of this costly prototype.

Cabinet du Dauphin (1682-1686)

During his time as the royal cabinetmaker, Boulle developed an expansive body of work. He was responsible for creating the majority of the furniture in the Palace of Versailles.

However, his crowning achievement is his decoration, the Cabinet du Dauphin (1682-1686).

He designed the mirrored walls, wood mosaic flooring, adding remarkable, intricate paneling and marquetry.

Unfortunately, the study dismantled in the late 18th century. Today, parts of the room are at the National Archives in Paris.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, Boulle did not sign many of his pieces. That, as well as the sheer quantity of 18th and 19th-century replicas, makes crediting him for specific works difficult.

Boulle marquetry work has its own aesthetic, but many museums, galleries, and collections list his pieces as “attributed to” Boulle.

Boulle’s skills in a variety of mediums helped revolutionized furniture design. His pieces transcended practicality and became works of art that continue to inspire to this day.

Styylish

Visit the Shop for your antique furniture needs. We carry a wide selection to fit any home or style. Just ask!

For more art history, resources, and inspiration, check out the Blog.